Oscillators can do more than just generate static waveforms

One of the great aspects of virtual instruments is that many, if not all, parameters are automatable. But which parameters are worth automating? Just about everyone appreciates twisting filter cutoff frequency and envelope attack or decay, but today’s soft synths have seemingly progressed faster than the ability of musicians to assimilate all the cool new tricks they can do. Case in point: oscillators.

If you think that oscillators are boring, static tone generators that are good only for providing a signal so that filters and envelopes can do something interesting to them, think again. Today’s virtual instrument companies are sprucing up their oscillators with capabilities like hard sync, frequency modulation, and ring modulation. These are powerful options that can make a synth leap out of a track by adding a more dynamic, edgy timbre. Let’s take a look at hard sync, probably the most popular of these effects, and a trademark sound of old school analog synths.

HARD TIMES IN SYNC-LAND

One of the best known-examples of the hard sync sound appears in the synth figure on that “vintage” 80s hit by the Cars, “Let’s Go.” Hard sync changes a tone’s harmonic structure, so it’s kind of like filtering; but the sound is more pronounced, with an almost vocal-type resonance.

Hard sync requires two oscillators. One oscillator tracks the keyboard and sets the pitch. However, we never actually hear this oscillator’s audio. Instead, we hear the sound of a slave oscillator, whose period (the length of one cycle) is always synchronized to the pitch oscillator.

Confused? Here’s a more obvious example of “hard sync,” but at a much lower frequency. Suppose you have a slow LFO hooked up to control filter cutoff. There will probably be a mode that re-triggers the LFO when you hit a key. This “hard syncs” the LFO to your playing: no matter where the LFO is in its cycle, when you hit a key, it re-starts.

Similarly, regardless of what the slave waveform is doing, when the pitch oscillator starts a new cycle, so does the slave. If you change the slave’s pitch, the waveform will still have the same period – and therefore the same perceived pitch – because it’s slaved to the pitch oscillator. However, the harmonic structure will change radically as the slave’s frequency changes.

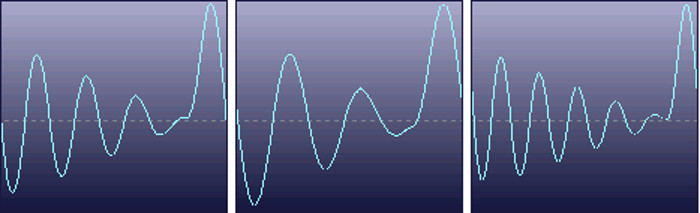

These three waveforms above represent three different slave oscillator frequencies, but the pitch oscillator frequency is the same in each case. Note that the period (the length of each waveform’s cycle) is the same, but the waveform’s shape – and therefore, harmonic structure – differs. This comes from changing the slave oscillator’s frequency.

There are a couple “rules” about hard sync settings:

- You generally don’t want any audio from the pitch oscillator. Listen to the output from the slave oscillator.

- If the slave oscillator pitch goes lower than the pitch oscillator, then the hard sync effect disappears. The slave oscillator always must be higher-pitched than the pitch oscillator.

- The pitch oscillator waveform isn’t really significant, as it’s used only as a timing reference. The slave oscillator waveform is less important than usual because the hard syn action has such a strong effect on the sound. However, a sawtooth or square wave will give more “bite” than a sine or triangle wave.

ANATOMY OF A PATCH

In addition to setting up the oscillators, to obtain interesting hard sync effects, you also need a modulation source to vary the slave oscillator frequency. Common choices are an envelope generator, mod wheel, or LFO (particularly an LFO that’s reset when you play new notes). However, you need a really wide-range pitch sweep – like four or five octaves – to get dramatic hard sync effects, and many modulation sources aren’t really designed to deliver that kind of output.

The simplest solution is to “double up” the number of envelope destinations. For example, if there are two possible output destinations, send both to the slave oscillator’s pitch, and turn up both output levels as high as possible. Also, if the slave oscillator has a control input, make sure that it too is set for as wide a range as possible.

The image at the top shows the crucial synth elements needed to create a hard sync preset, as shown with the Mai Tai synthesizer from Presonus Studio One.

Oscillator 1 is the pitch oscillator. Because we don’t need to hear it, the level control (outlined in orange) is set to zero. Osc 2, the slave oscillator, has its Sync button (outlined in yellow) enabled so it can sync to Osc 1’s pitch, Envelope 2 (outlined in blue) sweeps Osc 2’s pitch from high to low, as governed by the matrix modulation section (outlined in red). Here, Envelope 2 is shown modulating Osc 2’s pitch. This produces an automated sweep, but there’s a lot to recommend using the mod wheel to vary the slave oscillator’s pitch.

There are oscillator cross-modulation options other than hard sync; Frequency Modulation (FM) is also popular. In a nutshell, this causes one oscillator to modulate the other (without re-synching) so that the resulting signal has more complex sidebands. Increasing the level of the modulating signal increases the complexity of the signal.

In any event, next time you need to do a cutting synth solo, you don’t necessarily have to reach for the EQ or a distortion processor: set up hard sync, link it to your mod wheel, play expressively, and record the mod wheel movements as automation. You’ll be treated to a far more animated, biting sound that if you let it, can take over a track.