Until recently, tempo changes were a part of music. Have we lost anything by adopting the click track as standard?

There are certain villains in current music—like pitch correction, loudness maximization, and over-quantization. Of course, the technology itself isn’t the problem; it’s how that technology is applied, like overuse or laziness (“sure, we’ll just throw pitch correction on the whole vocal”).

As issue that doesn’t get mentioned as often, probably because people don’t think too much about its importance, involves tempo changes. These days, almost all popular music is cut to an unvarying click track, in order to keep a steady tempo. A click track makes it much easier to do overdubs, as well as use tempo synched effects. It’s also extremely helpful to solo musicians, because they by definition don’t have a bunch of people playing in a room together.

But do we lose anything by not having tempo variations? Is it a coincidence music that has stood the test of time was recorded without a click track? Are we overlooking a musical element that adds an emotional component? Even though it’s difficult to work tempo variations into a song, is this something we really need to consider?

So I started doing some research, and here’s what I found. Cakewalk by BandLab has a feature where you can drag audio into the timeline to generate a tempo map automatically. The results were revealing. Not only did the songs have tempo changes, those changes were far from random. Granted, they didn’t have the metronomic precision you’d expect from recording to a click track, but there were definite patterns. Whether unconscious or not, these patterns were deliberate enough to be repeated in similar sections of the song. Here are some examples.

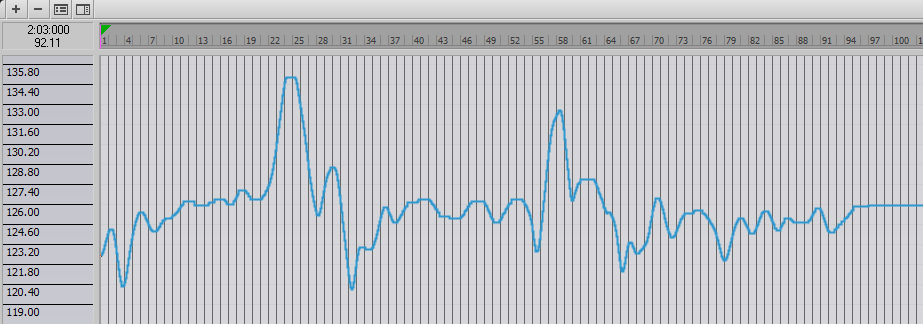

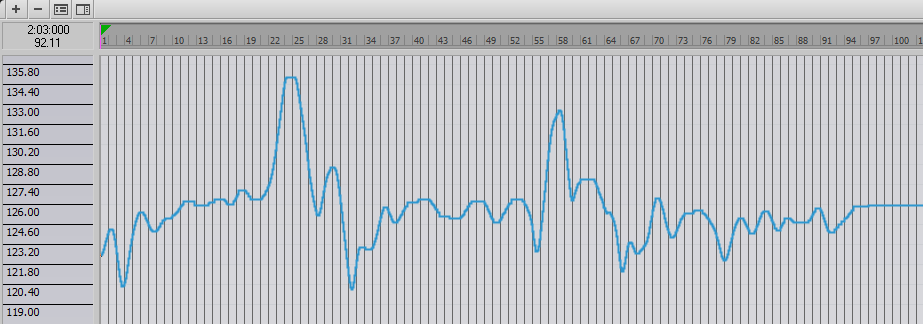

JAMES BROWN “PAPA’S GOT A BRAND NEW BAG”

James Brown’s rhythm section was often considered the tightest rhythm section ever to grace this planet. If any drummer could earn the title of “human click track,” it would be Clyde Stubblefield…right? But in reality, he had the ability to twist the beat around in uncanny yet predictable ways. He indeed played with precision, but it wasn’t that of a flat-lined, metronome-based tempo track.

The tempo map “breathes” with plenty of variations, but also note that the song’s overall tempo increases linearly over time. The band accelerates the tempo until the phrase “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” that starts at measures 10, 22, and 42, at which point the tempo then decelerates. There’s even the same change at measure 55 which is musically similar, but doesn’t use the same lyrics. After each break, the tempo slides back up again.

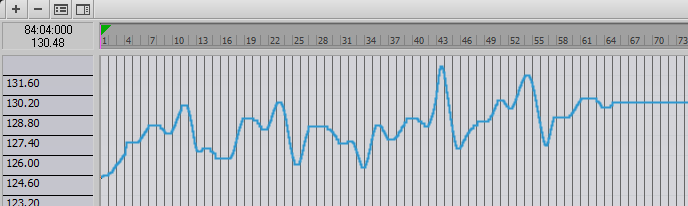

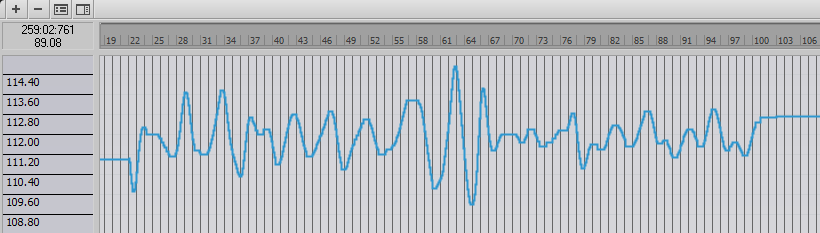

THE BEATLES “LOVE ME DO”

The Fab Four were not only quite consistent, but their tempo variations were clearly not just random.

While these tempo changes may appear to be random, they follow a definite pattern. Note the dramatic dramatic pause at “so please, love me do” around measure 16 and again at 49. I guarantee they didn’t program those tempo variations in a sequencer—they felt the changes, and then they sped up naturally after that section when it went into the “Love, love me do” verse. They also sped up a bit over the course of the track, which is something I saw in many songs.

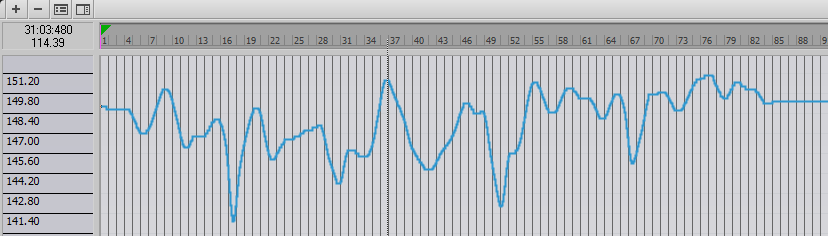

THE POLICE “WALKING ON THE MOON”

Although the overall tempo is consistent, there are two significant dips starting around measures 31 and 52.

These dips occur prior to leading into the bridge, but note that the tempo is higher the second time around. At measure 59, the band pulls back for the instrumental break. At measure 65, they start climbing out of it, and speed up as they head to the end of the song.

SMOKEY ROBINSON & THE MIRACLES “TEARS OF A CLOWN”

This is another song that follows a definite, deliberate pattern. The band accelerates until measure 22, which is just before the end of the verse, and then decelerates down the bridge into the line “tears of a clown” which starts at measure 31, after which the tempo starts accelerating again.

The second verse starting at measure 37 is pretty consistent, but again toward the end of the verse there’s the speed-up, the bridge decelerates, and the tempo is slowest when “tears of a clown” is repeated again—this is almost identical to the first set of tempo changes. After that, again the band is pretty consistent.

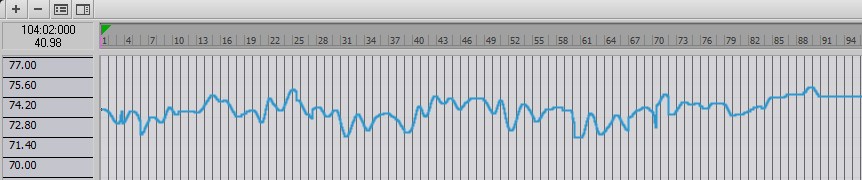

PAT BENATAR “SHADOWS OF THE NIGHT”

There wasn’t enough tempo information in the beginning for an analysis, so I drew a straight line in the beginning. In any event, either by accident or by design, the tempo tracks the vocal pitch quite closely.

But look what happens starting at measure 22—it’s like someone applied an LFO to the tempo, the changes are so consistent. The song pretty much tracks Benatar’s pitch; the tempo accelerates up to the higher notes in a phrase, then slides down as the pitch slides down. The most extreme variations occur during the guitar solo, which starts at the lowest tempo, then speeds up and slows down cyclically. I’ve always felt the vocal in this song is very compelling; I can’t help but wonder if part of that is because of the interplay with the tempo, which may amplify the effect of the vocal pitch changes.

TEMPO CHANGES DO MATTER

One element most of these songs have in common is accelerating tempo up to a crucial point in the song, then decelerating during a verse or chorus. This type of change was repeated so often, in so many songs I analyzed, that it seems to be an important musical element that’s almost inherent in music played without a click track. It makes perfect sense that this would add an emotional component that could not be obtained with a constant tempo. Also, the tempo often sped up, sometimes a little and sometimes a lot, as the song progressed.

Of course, there’s no easy way to measure the reaction tempo changes have on listeners. But in the process of adding tempo changes to my own songs, I believe there’s no doubt it has an effect. Remember, a key principle of music is tension and release. Speeding up adds a degree of tension and anticipation, while slowing down creates a corresponding release. Tempo changes can help music “breathe” more; it has always been a natural element of musicians playing together. It’s only in the past few decades that music has lost this vital characteristic.

Adding tempo changes to computer-based songs is more difficult than getting together with musicians in a room and playing what you feel, but it’s very doable—you can even add tempo changes after the song is complete. For more information, see the post How to Add Tempo Variations with DAWs and Use Tempo Change “Time Traps” for Extra Drama.