Even a few milliseconds of a sound leading or lagging the rhythm can change music’s emotional impact

Timing is everything…especially with music. Yet mathematically perfect timing is not everything, otherwise drum machines would have replaced drummers. World-class drummers enhance music by playing around with time—subtly speeding up or slowing down to change a tune’s feel, and leading or lagging specific beats to push a tune, or make it lay back a bit more in the groove.

Even a few milliseconds make a difference. This may be surprising, but once you experiment with timing shifts, it’s obvious that small timing differences matter.

Some people quantize MIDI data to a rhythmic grid, which can make music feel mechanical. Fortunately, a host program’s MIDI editing features can help put the feel back in to sequenced music.

Before proceeding I’d like to acknowledge Michael Stewart, whose seminal research on the topic first made me aware of the importance of small timing shifts.

HOW TIMING SHIFTS PRODUCE “FEEL”

“Feel” is not based on randomizing note start times. Accomplished drummers add variations in a mostly non-random, subconscious way, so these changes tap directly into the source of the musician’s feel. For example, jazz drummers often hit a ride cymbal’s bell or high-hat a bit ahead of the beat to push a song, and give it more urgency.

Rock drummers frequently hit the snare behind the beat (a bit late) to give a big sound. Our brain interprets slight delays as indicating a big space—since we’ve seen someone make noise at a distance, and know that sound takes time to travel through a big space before it reaches us.

Some instrumentalists create their own note shifts within an overall tempo shift. In other words, if the overall tempo is speeding up, a guitar player might speed up a bit more than the tempo change to emphasize the change, then pull back, speed up, pull back, etc. These changes will be felt more than heard, but just as subtle tempo tweaks can have a big influence on the sound, subtle note placement changes in relationship to a rhythmic grid can alter the feel.

TRACK TIMING TRICKS

Although we’re referencing MIDI, many of these principles apply to audio. There are two main ways to shift events or notes within a track:

- Click on the clips or notes you want to shift, and drag them. Because the shift amount will be small, zoom in and turn off snap. With longer tracks, use the Split tool to cut the audio into a specific region you want to shift. Otherwise, you might shift portions you don’t want to change.

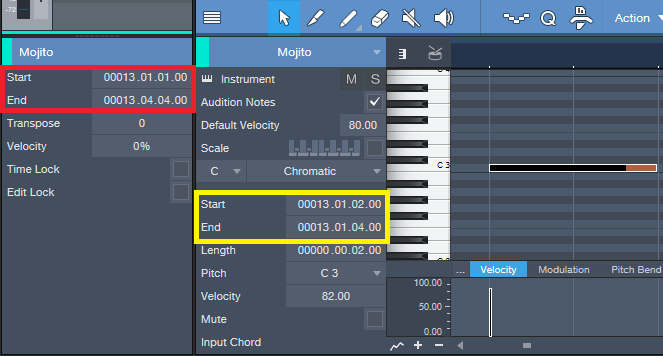

- Enter an offset or start time for Events or notes (see image above). In Studio One, and many other programs, you can enter precise start and end times for events (outlined in red in Studio One’s Inspector and in yellow for the Edit view), and start and end times for notes in the Edit view. If several Events are selected, you can usually shift them simultaneously by changing times for any of the selected events.

Granted, the following timing change applications are more premeditated than musicians playing instinctively, but the goal is the same—add more feel.

- What to shift. With drums, keep the kick drum on the beat as a reference, and shift the timing of the snare, toms, or percussion by a few milliseconds compared to the kick.

- More urgent feel. For techno, house, reggaeton, soca, and other dance-oriented music, try moving double-time percussion parts (shaker, tambourine, etc.) slightly ahead of the beat to give a more urgent feel.

- More laid-back feel. Shift percussion a few milliseconds late compared to the grid.

- “Bigger” sound. Shift the snare a few milliseconds late compared to the grid.

- Avoid part interference. If two percussion sounds in a rhythm pattern hit often on the same beat, try sliding one part ahead or behind the beat by a small amount (a few ms) to prevent the parts from interfering with each other.

- Cymbal emphasis/de-emphasis. Hitting a crash cymbal slightly ahead of the beat makes it stand out. Moving it slightly later meshes it more with the track.

- Melody/rhythm emphasis/de-emphasis. If the kick and bass hit at the same time, emphasize the melody by shifting the bass slightly earlier than the kick, or emphasize the rhythm by shifting the bass slightly later than the kick. Try it! The instrument that hits first sounds louder, even though the level doesn’t change.