Distortion and EQ are crucial for guitar – make sure you get the EQ right

The most important signal processors for any guitar are distortion and EQ. If you don’t agree, then consider this: what is a guitar amp but a distortion box, coupled with EQ from the cabinet/speaker combination?

Although amps are fun, they tend to specialize in one particular sound, which is why rack preamps and parametrics (or a good multieffects) can be invaluable. With a little tweaking, you can shade the sound to best suit the music at hand – something that’s a bit more difficult to do with an amp. Following are some tips on how to use EQ to better integrate your guitar with your overall mix.

STANDOUT LEAD GUITARS

Many times, making a lead guitar stand out in a track has nothing to do with turning up the volume. A rock guitar can be a pretty broad-bandwidth instrument, and overlap with the frequency ranges of vocals, piano, upper bass range, etc. If you turn up the volume too much, you run the risk of drowning out other important sounds.

EQ can accent a range of the guitar that doesn’t overlap other instruments, thus letting the guitar stand out without disturbing the rest of the track. As shown in the above image, a few dB boost around 3 to 4 kHz (circled in orange) can really accentuate a guitar lead; because that’s above the range of the toms, bass, and most rhythm-oriented keyboard parts, there’s no interference with these instruments. Also note that the lower frequencies are trimmed (circled in yellow) to avoid stepping on bass, kick, and low tomes. During solos where no vocals appear, a 1 to 2 kHz boost can often give the guitar a more “vocal-like” quality, as well as make it stand out a bit more in the track.

MORE EXPRESSIVE DISTORTION WITH EQ

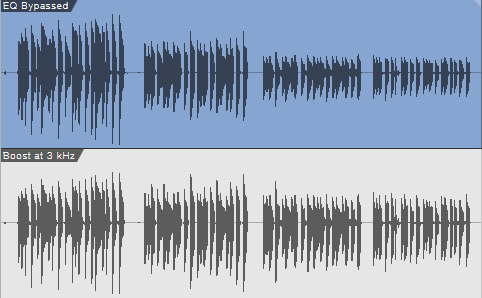

Patching EQ before distortion can make the distortion seem more “touch-sensitive.” Generally, distortion clips all frequencies more or less equally. Adding a gentle midrange boost before the distortion causes the notes in the boosted range to distort at lower levels, which makes the distortion seem more responsive at the selected frequencies (Fig. 1). Start by boosting in the range of 500 Hz to 4 kHz.

You can also use this technique to “clean up” a guitar sound somewhat by adding a bass cut prior to distortion. The lower strings will cause less intermodulation distortion, creating a cleaner, more “biting” sound.

“HARD SYNC” DISTORTION SOUND

Using a sharp, narrow boost prior to distortion adds an effect that’s almost like a synthesizer’s “hard sync” option. Being able to sweep the boost frequency is even better, as it dramatically changes the guitar’s timbre – sort of like a wa-wa, except that the distortion adds a kind of “resonant toughness.”

USING GUITAR EQ TO SUPPORT VOCALS

Here’s another example of using EQ to make an instrument a “better neighbor” in an arrangement. Suppose you’re playing rhythm guitar behind a vocalist, but the guitar and voice conflict because they occupy a similar frequency range. If you add a shallow, fairly broad midrange cut to the guitar, it opens up more bandwidth for the vocal frequencies. The guitar’s high and low frequencies “frame” the vocals.

REDUCING HUM WITH EQ NOTCH FILTERING

60 Hz hum is a drag, but a parametric equalizer can help remove it. Simply set the equalizer for maximum cut and sharpest bandwidth, then dial in 60 Hz (you’ll know you’re at the right frequency because the hum will disappear). If there’s also an harmonic component at 120 Hz, use a second parametric stage to take care of that.

REDUCE HISS IN VINTAGE EFFECTS

A stereo graphic or shelving EQ can help reduce hiss in older effects by using one channel to boost treble going in to the effect, and the other channel to cut treble after the effect by an equal but opposite amount.

Start the boost at around 2 to 5 kHz, and boost a reasonable amount (6 to 10 dB), short of overload. Cut starting at the same frequency, and by the same amount. This will reduce any hiss coming out of the effect and in theory, the original signal will sound unaltered if the boosting and cutting are symmetrical.

TAME YOUR ECHOES

You don’t always want a meaty, substantial echo; something subservient to your main guitar sound might be more appropriate. To trim your echo’s frequency response you’ll need a mixer and Y-cord. Split the guitar into two paths; one goes directly to the mixer, and the other to an equalizer/delay line combination before it hits the mixer. Cut the bass and lower midrange going to the delay line, and the echo will shimmer on top of your main sound

FIXING DEAD SPOTS ON GUITAR NECKS

You know how basses (and guitars) sometimes have “dead spots” on the neck that just don’t quite seem to have the same power as the other notes? This is a job for parametric equalization. Turn the volume down on your amp, and turn the EQ’s boost and bandwidth controls up full. Play the dead note repeatedly while sweeping the parametric’s frequency control; when the parametric hits the right frequency, the note will jump out (in a possibly obnoxious fashion, which is why a low monitoring level is important).

After finding the right frequency, reduce the amount of boost until the dead note is the same level as the other notes. If the note sounds too “peaky,” reduce the bandwidth control as well.

DON’T FORGET THE GUITAR ITSELF!

There are a lot of modifications you can do to a stock guitar to greatly alter the sound, such as using tapped pickups, rewiring the tone control, changing pickup phase, etc. Articles on this site can help!