Limiting, compression, multiband dynamics – find out how each one affects sustain

Dynamics control for guitar used to be easy: You put a compressor stomp box like an Orange Squeezer in the signal chain, and hit the footswitch for more sustain. Now in the studio and sometimes even on stage, software plug-ins provide several flavors of dynamics control—which is the right tool for the right job?

Level-wise, guitar strings are tough cases: they have high peak levels from the pluck attack, and low average levels from the rapid decay. Dynamics processors can affect both the attack and decay.

THE LIMITER

A limiter is like an engine’s governor—no matter how much signal you put into it (within reason), the limiter clamps signals above a threshold to a specific output level. This has three main uses.

- Control spikes and transients (e.g., slap bass, heavy picking) that could overload subsequent stages.

- Provide an overall louder signal without altering the note’s decay shape. For example, if you set the threshold at -3dB, signals below that won’t be affected but higher-level signals will be clamped to -3dB. This opens up 3dB of headroom, so now you can amplify the entire signal by 3dB to make it louder without distortion.

- Put an “audio magnifying glass” on your signal—the lower-level decay signal will be louder.

THE COMPRESSOR

A compressor is more complex, because it has more control over what happens to the audio after it exceeds a particular threshold, as controlled by the ratio parameter. For example, you increase the guitar level by 4 dB but the output increases only by 2 dB, that’s considered 2:1 compression. But if you increase the guitar level by 12 dB and the output increases by only 2 dB, then that’s 6:1 compression. Ths keeps peaks under control while providing more sustain. Unlike the limiter, which doesn’t affect the decay’s shape, compression flattens the decay more.

MULTIBAND DYNAMICS

Multiband limiters and compressors separate a signal into several frequency bands (typical 4 or 5), each with its own dynamics section. Because the dynamics control affects only frequency ranges that need it, the effect is more transparent. For example with a standard limiter, if you hit the low E string really hard the limiting action will affect other strings too. A multiband limiter would limit in the range of the low E, but not the higher strings.

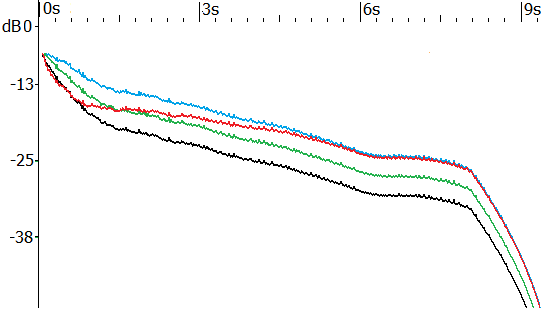

Figure 1 shows four loudness curves. The black one is an unprocessed E chord. Green adds 3dB of limiting, which reduces the peak; the decay curve level is higher than the unprocessed sound, but has the same shape. The blue curve applies 6dB of limiting. Again, the decay curve tracks the unprocessed signal, but is simply louder. The peak has a much gentler slope.

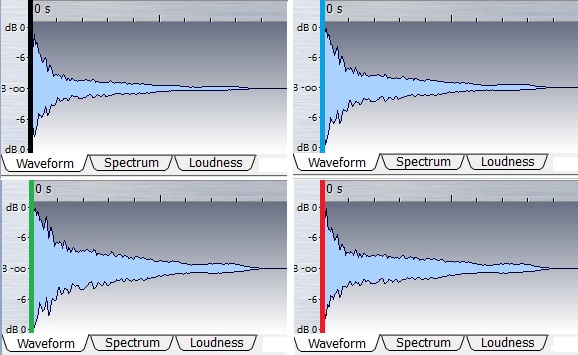

The red line shows multiband compression. The peak gets clamped pretty quickly, and then the level starts evening out to a flatter shape that increases sustain. At around -20dB the curve tracks the unprocessed curve’s signal, but note that its level remains higher. Figure 2 relates these loudness curves to waveforms.

Let’s compare a couple waveforms. The first audio example is guitar with some limiting. The second one is the same guitar chord through multiband compression; pay particular attention to the initial peaks, and the sustain at the end of the note.

HOW TO CHOOSE THE BEST DYNAMICS OPTION

Each method provides more sustain, but with different characters. Limiting gives more presence, a bigger sound, and squashes the peaks more so the guitar isn’t as percussive. Compression tends to give a smoother, rounder, more sustaining sound. Multiband compression retains more of the guitar’s characteristic peak, coupled with more sustain and a flatter decay. You’ll still need to decide what dynamics control to use on a case-by-case basis, but hopefully this info can help point you in the right direction.