Have a tighter rhythm section than an E string tuned up an octave

The highest compliment you can pay to a rhythm section is that they’re “tight.” Let’s look at a hard disk editing technique that can tweak a bass part to groove exactly with the drums, and give a super-tight rhythm section.

VISUAL ALIGNMENT FOR BASS AND DRUMS

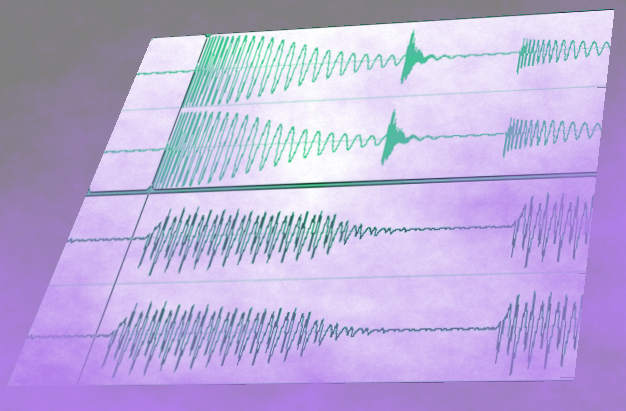

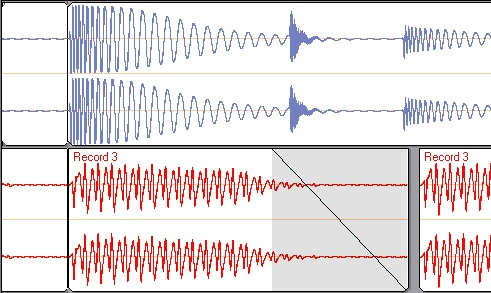

One advantage of computer-based, multitrack hard disk recording systems is that you can see multiple tracks simultaneously. For example, you can place the drum and bass tracks next to each other to compare where their notes land.

Referring to the upper drum track (blue) in Fig. 1, it’s easy to see where the beats fall; note the obvious spikes where different hits occur. Now look closely at the lower bass track (red)—the bass attacks clearly lag a bit behind the drums. Of course, many timing variations are welcome as they can contribute to a song’s groove. What we’re concerned about is reining in any bass notes whose timing is sufficiently different from the drums to sound “off.”

SPLIT TRACKS AND MOVE NOTES

The solution for locking bass and drums together is to isolate any bass note whose timing is “off,” then move it so that its attack lines up with the beat. Unlike traditional quantizing, which shifts notes to a rhythmic grid, with this technique you have the option to move notes so that they follow the drums exactly, even if the drums themselves lead or lag the beat a bit.

Isolating the notes is simple. Most hard disk recording programs offer some sort of split function, where you can divide a piece of audio into separate sections. Upon isolating a note, you can then move it into position. You’ll generally want to make sure that any “snap” or quantize function is off, so you can split the audio anywhere, not just at arbitrary rhythmic points.

CORRECTING FOR LATE NOTES

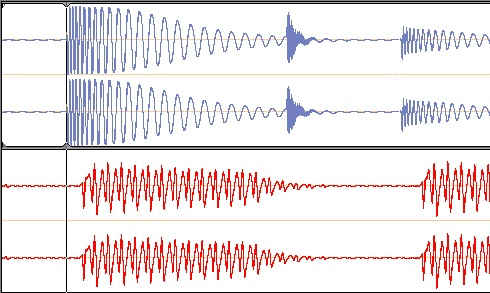

Referring to Fig. 2, we’ll now correct for a bass note that’s late compared to the beat. Here are the steps.

1. Add three split points. From left to right, these are:

- The beat where the note attack should fall.

- The beginning of the note to be moved (in Fig. 2, the space between these first two split points is highlighted in black).

- The beginning of the next bass note.

2. Delete the highlighted space between the desired note start and the current note start.

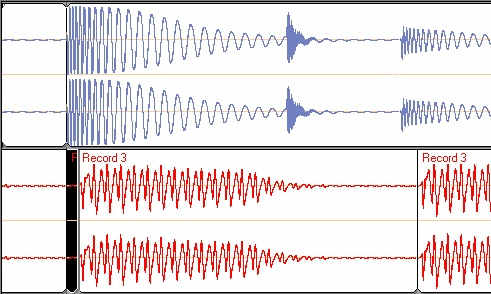

3. Move the note to the left so that its attack lines up with the correct beat (Fig. 3).

Now we have a new problem: moving the note earlier has opened up a slight space in front of the next note. You may want to move this note as well, but let’s assume it sounds fine as is. Although most of the time whatever else is playing will mask any gap between notes, if you hear any kind of abrupt, audible glitch, there are a couple of possible fixes.

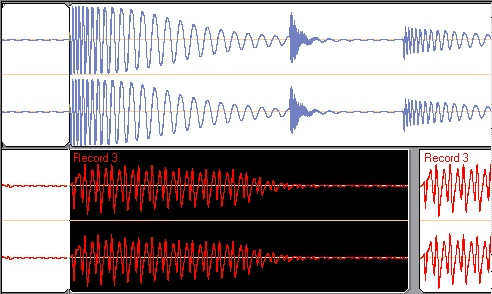

The simplest is to add a quick fade toward the end of the note you moved (highlighted in gray in Fig. 4, with a diagonal line showing the fade itself). This makes the gap less abrupt, but may not work if you need the note to sustain up to the beginning of the next note.

Actually lengthening a note requires more complex surgery. The following technique may or may not work, but if you’re persistent, you can usually achieve success.

1. Split the note so that the sustained tail is separate from the attack. The object is to isolate the note’s most consistent, sustained portion.

2. Copy the sustained portion (some programs allow you to copy a region without having to split it first).

3. Crossfade the end of the note that needs to be lengthened with the beginning of the sustained segment. If needed, you can then add a fade to the end of the conjoined note, or have it butt up against the beginning of the next note. Crossfading can often make the grafted note segment sound like it was part of the original note.

CORRECTING FOR EARLY NOTES

If a note comes in ahead of the beat, split the audio just ahead of that note, and again just ahead of the next note. As we’re going to be moving the note later in time, and don’t want the end of the note being moved to overlap the next note, use the program’s non-destructive “slip” or trim editing function to shorten the end of the note being moved. If the note butts up against the beginning of the next note, odds are it will sound okay. If it doesn’t, or if there’s an audible click or pop, you may need to add a very quick fade to the end of the note you moved.

DON’T OVERCORRECT!

It’s possible to get sucked into being way too concerned about little timing errors. Don’t be – just fix the notes that sound wrong, not the notes that look wrong. You’ll still end up with an ultra-tight rhythm section – and certainly anyone reading this knows how much that can improve a tune’s entire sound.