It may sound crazy to add pink noise while mixing, but there’s a method to this madness

If you’re visiting this site, you’ve probably found some value in what I’ve written, and won’t dismiss the following out of hand as you dissolve in gales of laughter. But most people who’ve been brave enough to try this technique swear that it does work…see what you think.

ONE REASON WHY MIXING IS CHALLENGING

A mix doesn’t compare levels to an absolute standard; all the tracks are interrelated (e.g., lead instruments typically have higher levels than rhythm instruments). Top mixing engineers are in demand because they’ve trained their ears to discriminate among tiny level and frequency response differences. They “juggle” the levels of multiple tracks to make sure that each one occupies its proper level with respect to the other tracks. The more tracks, the more intricate the juggling act.

However, there are certain essential elements of any mix—some instruments that just have to be prominent, and have similar levels because of their importance. Ensuring that these elements are clearly audible, and perfectly balanced, is crucial in creating a mix that sounds good over a variety of systems. Perhaps the lovely high end of some bell won’t translate on a cheap boombox, but if the average listener can make out the vocals, leads, the beat, and the bass, the high points are covered.

Remember too that our ears are less sensitive to changes in relatively loud levels. Many veteran mixers work on a mix initially at low levels, because it’s easier to tell if the important instruments are out of balance.

THIS TECHNIQUE’S BACKSTORY

When working in a studio in Florida, I noticed that mixes done with the air conditioner on often sounded better than ones done when it was off. Then I made the connection with how many musicians use the “play the music in the car” test as the final judge of whether a mix is going to work or not. In both cases the background noise masks low-level signals. This makes it easier to tell which signals make it above the noise.

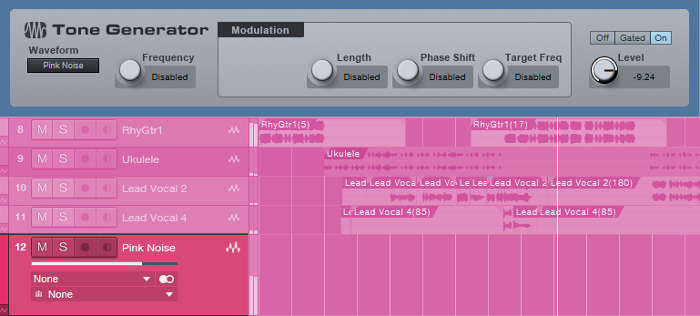

Curious whether this could be defined more precisely, I started injecting pink noise into the console while mixing. This just about forces you to listen at relatively low levels, because the noise is obnoxious—but more importantly, the noise adds a sort of “cloud cover” over the music, and as mountain peaks poke out of a cloud cover, so do sonic peaks poke out of the noise. So, mixing with a pink noise source (like Studio One’s Tone Generator, or download a WAV file from the web) as one of the channels, panned to center, can help check whether a song’s crucial elements are mixed with equal emphasis.

HOW TO MIX WITH NOISE

Inject noise sporadically; you can’t get an accurate idea of the complete mix while injecting noise, because the noise covers up high frequency sounds like hi-hat. But it can help you make sure that all the important instruments are being heard properly.

Typically, I’ll take a mix to the point where I’m fairly satisfied with the sound. Then I’ll add in pink noise, and start analyzing.

While listening, pay special attention to vocals, snare, kick, bass, and leads (with this much noise, you’re not going to hear much else in the song anyway). It’s easy to adjust their relative levels, because there’s a limited range between overload at higher levels, and dropping below the noise at lower levels. If all the crucial sounds make it into that “window,” and can be heard clearly above the noise without distorting, you have a head start toward an equal balance.

Also note that the “noise test” can uncover problems. If you can hear a hi-hat or other minor part fairly high above the noise, it’s probably too loud.

I’ll generally run through the song a few more times, carefully tweaking each track for the right relative balance. Then it’s time to take out the noise. First, it’s an incredible relief not to hear that annoying hiss! Second, and more importantly, you can now get to work balancing the supporting instruments so that they work well with the lead sounds you’ve tweaked.

Although so far I’ve mentioned only instruments that are above the noise floor, the noise creates three distinct zones: totally masked by the noise (inaudible), above the noise (clearly audible), and “melded,” where an instrument isn’t loud enough to stand out or soft enough to be masked, so it blends in with the noise. Mixing rhythm parts so that they sound melded can work well, if the noise is at a level suitable for the rhythm parts.

Overall, I spend very little mixing time using the injected noise. But often, it’s the factor responsible for making the mix sound good over multiple systems. Mixing with noise may sound crazy, but give it a try. With a little practice, there are ways to make noise work for you.